SECTION 3: INTERNET MONITORING

4 in every 5 parents monitored what their kids were doing online.

| Internet monitoring- Parent respondent | Wave 1 (n=1,581) |

Wave 2 (n=1,195) |

Wave 3 (n=1,150) |

| Ask child where they go and what they see on the Internet | 88% | 87% | 83% |

| Check history function on browser[2] | 77% | 72% | 68% |

| Check child’s files, CD’s, or disks to see what’s on them | 59% | 56% | 54 |

[2] All respondents were asked this question at Wave 1. At Wave 2 and Wave 3 this question was only asked of those with home internet access (NWave2= 1,154; NWave3= 1,112).

Almost nine in ten parents reported talking to their children about where they go and what they see online. All three behaviors were commonly reported however, with more than half of parents endorsing each one.

Youth agree… mostly…

| Internet monitoring- Child respondent [3] | Wave 1 (n=1,581) |

Wave 2 (n=1,195) |

Wave 3 (n=1,150) |

|

| Yes Not Sure | Yes Not Sure | Yes Not Sure | ||

| Parent asks where child goes and what they see on the Internet | 75% 7% | 73% 6% | 72% 6% | |

| Parent checks history function on browser | 35% 42% | 37% 38% | 34% 39% | |

| Parent checks child’s files, CD’s, or disks to see what’s on them | 28% 38% | 26% 36% | 24% 36% | |

[3] The ‘not sure’ response option was not available for parent respondents.

Similar to parents, the most common parental monitoring activity reported by youth was their parents asking them questions about where they go and what they do on the Internet (see Table on page 13). Rates reported by parents and child differed notably for monitoring activities where parents did not need to directly ask the youth questions (i.e., asking child about what sites they visit on the Internet). Because parents are able to check the history function on the Internet browser indirectly without needing to ask their child questions, parents are able to complete these monitoring activities without the child’s knowledge. Thus, youth are less aware of whether these types of parental monitoring activities take place.

Half of parents used blocking software, but this decreased over time.

The use of blocking software fell from 51% to 42% over the 36 month period. As shown in the figure above, the rate of unsure parents remained stable at 10% across time, as did the percent of adults reporting that the computer used to have software but it had been subsequently removed. It is unclear how this last group can be reconciled with the decrease in software use. Perhaps, it’s a bit ‘out of sight, out of mind’. Blocking software can make web surfing cumbersome and frustrating. Maybe because it’s a much more seamless Internet use experience without the software, parents forgot that it was ever on the computer.

Fewer youth than parents reported blocking software on the computer.

About 10 percentage points fewer youth reported the presence of blocking software on the home computer. It is possible that some parents were using the software covertly. It’s also possible that some parents had not installed the software correctly; or that the parents and children had a different understanding of what blocking software is.

About 1 of every 4 of youth who know they have blocking software or parental controls on their home computer knew how to get around or disable blocking software or parental controls.

| Know how to get around or disable blocking software or parental controls – Child respondent | Wave 1 (n=667) |

Wave 2 (n=505) |

Wave 3 (n=450) |

| Yes | 24% | 24% | 25% |

| Not sure | 11% | 18% | 17% |

Being able to get around or disable restrictions on the computer was not related to age: the rates were stable across time. This may be partly because of increasingly sophisticated software that made it more difficult to subvert.

SECTION 4: BELIEFS ABOUT MEDIA USE

7 of every 10 parents felt that in general, parents should worry most about what children see online.

| What parents should worry most about – Parent respondent | Wave 1 (n=1,581) |

Wave 2 (n=1,195) |

Wave 3 (n=1,150) |

| What children see online | 68% | 67% | 70% |

| What children see on TV | 20% | 18% | 16% |

| What children see in video games | — | 5% | 4% |

| Not sure | 12% | 11% | 10% |

The majority of parents thought that caregivers should worry most about what young people see online. Only one in 5 thought that TV content should be of concern, and one in 20 that video game content was worrisome.

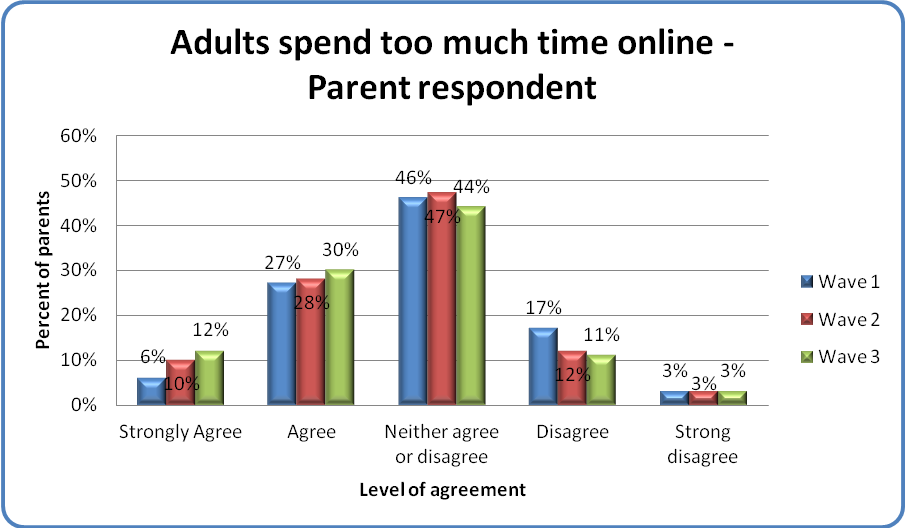

The majority of parents neither agreed nor disagreed that adults spend too much time online.

As shown in the figure above, 1 in 3 parents (33-42%) agreed or strongly agreed that adults spend too much time online.

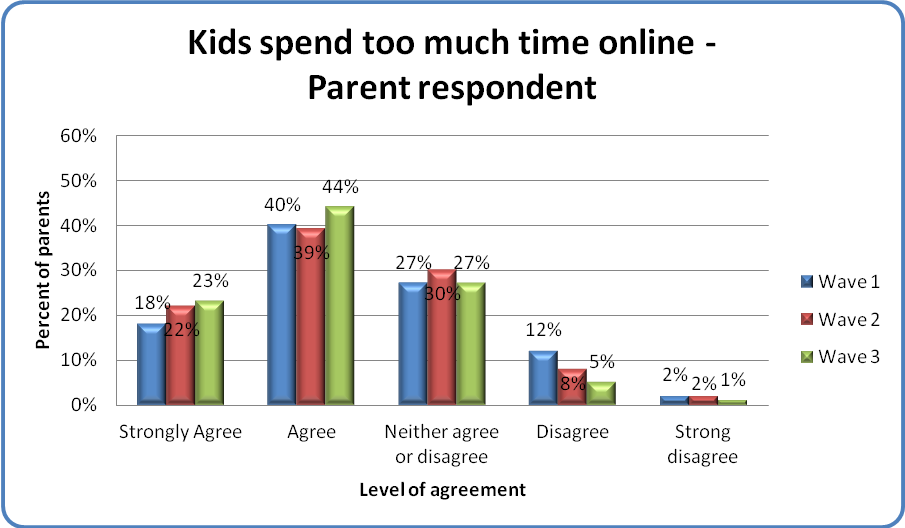

But, the majority of parents believed that kids spend too much time online.

In contrast, more than 1 of every 2 parents (58-67%) agreed or strongly agreed that kids spend too much time online.

CONCLUSION:

There is lots of good news: most households have rules about media use, and most parents and children agree about what these rules are. Most parents enforce, and most youth follow these rules. Also too, monitoring and co-use of the Internet and television was commonly reported by parents (but this was less true for video games).

It seems that Internet safety efforts have been effective at educating parents about the importance of monitoring and talking to their children about what they do and see online. Perhaps future efforts should be more integrated to focus on media use more generally and helping parents appreciate the need for involvement in how their young people are using and experiencing all types of media. This may be especially true for video games. The most common rule for Internet and television was a restriction about content that youth were allowed to see. For games however, the most common rule was ensuring that home work and other chores were done before youth were allowed to play. Similarly, the fewest number of caregivers thought that parents should be worried about what youth see in games. Certainly, media play an influential and often positive role in the lives of young people. Empowering parents with the tools to help their children safe is an integral part of this.

Other Bulletins in this Series:

- Methodological Details

- Parent and Youth Media Use Patterns

- Exposure to Violence and Sex in Media

- Youth Violence Victimization and Perpetration

- Mental Health and Psychosocial Indicators

Selection of Other Publications:

Ybarra, M., Diener-West, M., Markow, D., Leaf, P., Hamburger, M., & Boxer, P. (2008). Linkages between internet and other media violence with seriously violent behavior by youth. Pediatrics, 122(5), 929-937.

Ybarra, M.L., Espelage, D., & Mitchell, K.J. (2007). The co-occurrence of internet harassment and unwanted sexual solicitation victimization and perpetration: Associations with psychosocial indicators. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41 (6,Suppl), S31-S41.

Mitchell, K.J. & Ybarra, M.L. (2009). Social networking sites: Finding a balance between their risks and benefits. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(1) 87-89.

Acknowledgements:

The GuwM Study was funded by a Cooperative Agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U49/CE000206; PI: Ybarra). Points of view or opinions in this bulletin are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of policies of the Centers for Disease Control.

We would like to thank the entire Growing up with Media Study team: Internet Solutions for Kids, Harris Interactive, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and the CDC, who contributed to the planning and implementation of the study. Finally, we thank the families for their time and willingness to participate in this study.

This bulletin was prepared jointly by (in alphabetical order) : Dr. Josephine Korchmaros, Ms. Elise Lopez, Dr. Kimberly Mitchell, Ms. Tonya Prescott, and Dr. Michele Ybarra.

Suggested citation: Center for Innovative Public Health Research (CiPHR). Growing up with Media: Parent and Youth Reported Household Rules Characteristics. San Clemente, CA: CiPHR.