Favorite Computer, Video, or Internet Game:

At Wave 2, youth who reported ever playing games were asked if they had a favorite game. The majority (89%) reported having a favorite game.

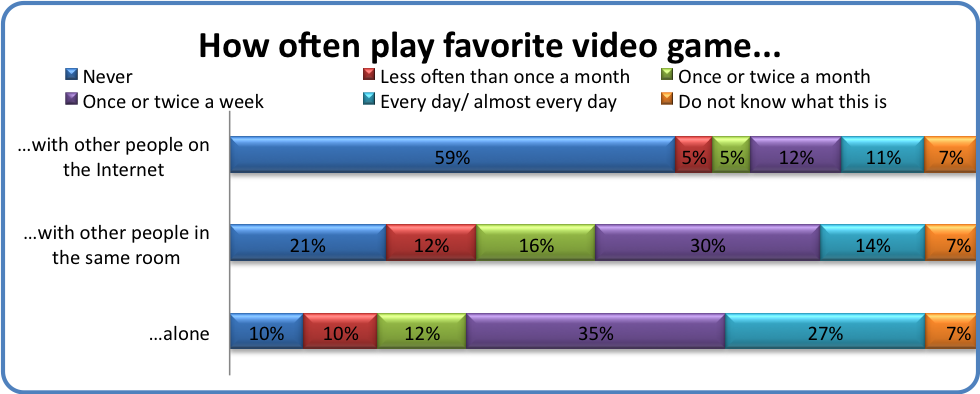

Most youth (83%) played their favorite game alone at least some of the time. While some youth (34%) reported playing games with other people online, they were much more likely to play games with other people in the same room (72%).

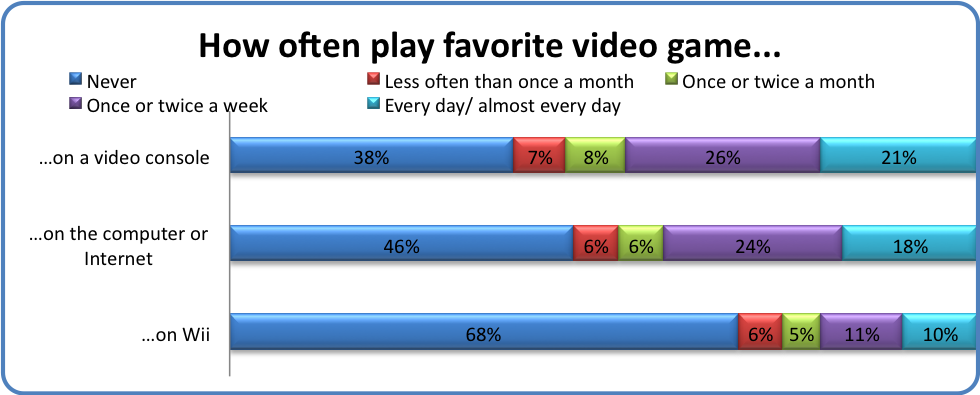

One’s favorite game did not seem to be determined by how it was accessed: similar percentages of youth reported having a favorite game on a video console versus computer or Internet. Much fewer youth however, said that their favorite game was on Wii.

Type of favorite game varied widely with fantasy / role-playing games being the most commonly endorsed by youth (28%).

| Type of favorite game | Wave 2(n=1,054) |

| Fantasy/ role playing game | 28% |

| Other | 24% |

| Sports game | 16% |

| First-person shooter game | 15% |

| Classic game or puzzle and logic | 15% |

| Kids game | 14% |

| Massively Multi-player Online Games (MMOG) | 13% |

| Educational game | 6% |

Similar percentages of youth reported their favorite game being a sports game; classic game, or puzzles and logic-based; or a first person shooter game. Interestingly, 1 of every 4 youth reported their favorite game was considered an ‘other’ type of game not provided in the list of response options. For good reason, the majority of research and advocacy attention is focused on youth who play violent games such as first-person shooter games. Our data suggest good news however: it is uncommon for youth to have a violent game as their favorite game.

SECTION 3: CHARACTERISTICS OF Wii AND MMOG PLAY

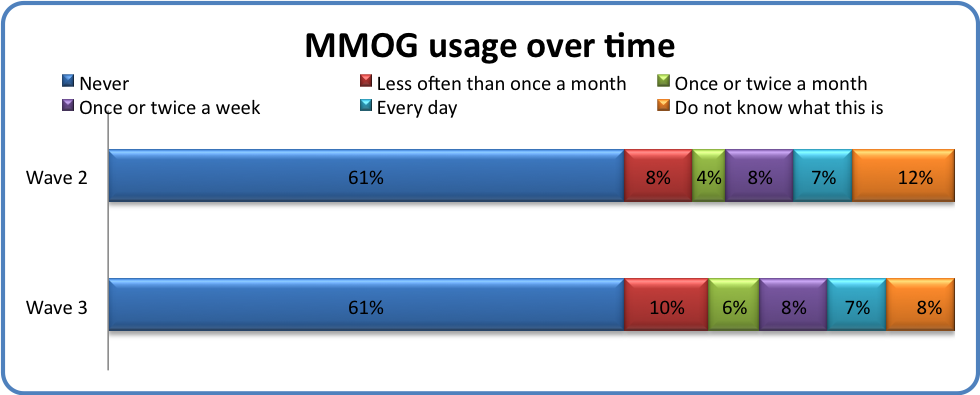

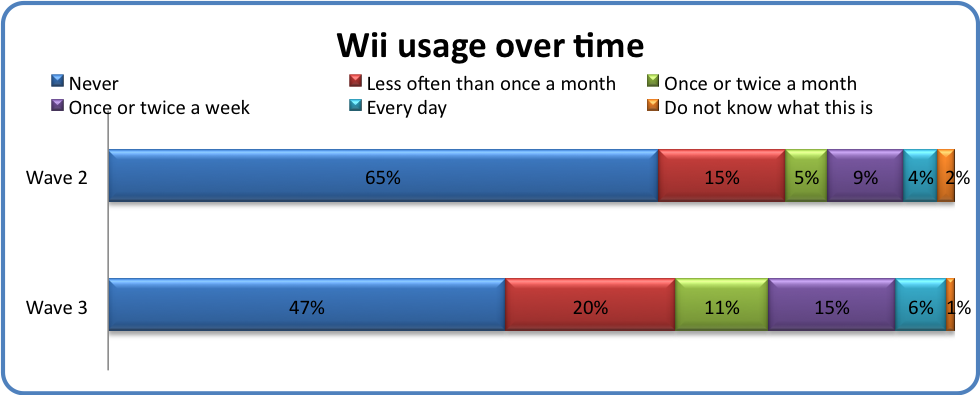

Wii usage increased over time while use of Massively Multi-player Online Games (MMOGs) remained relatively stable.

It is clear that Wii became increasingly popular among game players over the course of this study. Indeed, from Wave 2 to Wave 3, use of Wii increased by 20 percentage points.

In contrast, MMOG use was relatively stable over time: about 1 in 3 gamers played an MMOG. Although still a minority, more youth who played games did not know what MMOGs were than did Wii.

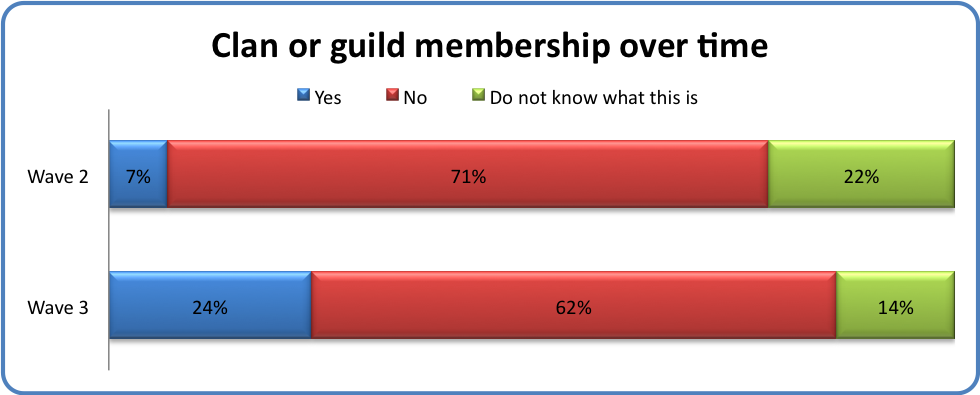

Clan or guild membership increased over time among game players.

Clans are defined as a group of game players that band together to form an ongoing team that together play a multiplayer game. The concept of a guild is similar to a clan, but allows for a larger group of members.

There were significant differences over time in regular membership of a clan or guild, as well as knowledge of clans or guilds: less than 1 of every 10 gamers were members of a clan or guild at Wave 2 compared to 1 of 4 youth at Wave 3. These differences may be partially attributed to a change in the survey skip pattern which resulted in a smaller sample size that were asked this question at Wave 3.Specifically, at Wave 2 this question was asked of all youth who reported they ever played games (n=1124). However, at Wave 3,this question was asked only of youth who reported playing MMOGs (n=349). Once restricting the sample at Wave 2 to include only those who played MMOG’s (n=136), the clan or guild membership rates are more similar (Yes=38%, No=52%; Do not know what this is=9%) and actual indicate a decrease in clan or guild membership over time.

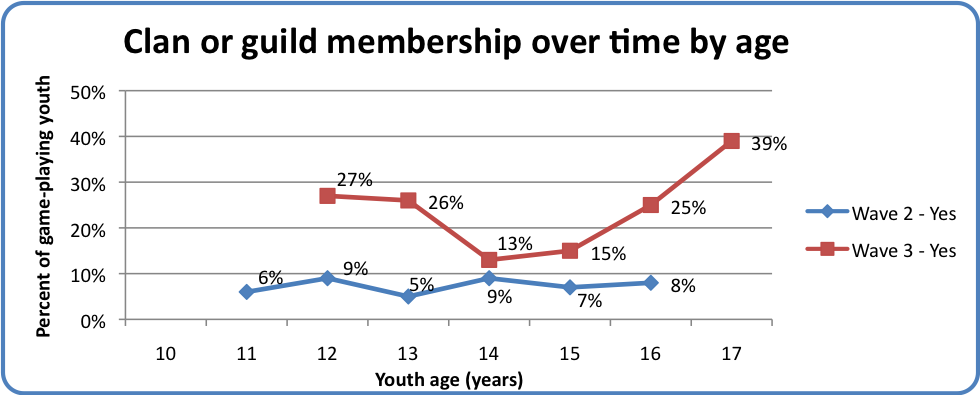

As shown in the figure on the next page, no age differences in clan or guild membership were apparent at Wave 2. A different pattern was noted one year later at Wave 3: membership decreased from 12-14 year olds, but then more than doubled for 15-17 year olds. Again, the reason for this change is unknown, but it could be due to vulnerabilities to change related to the reduced sample size at Wave 3.

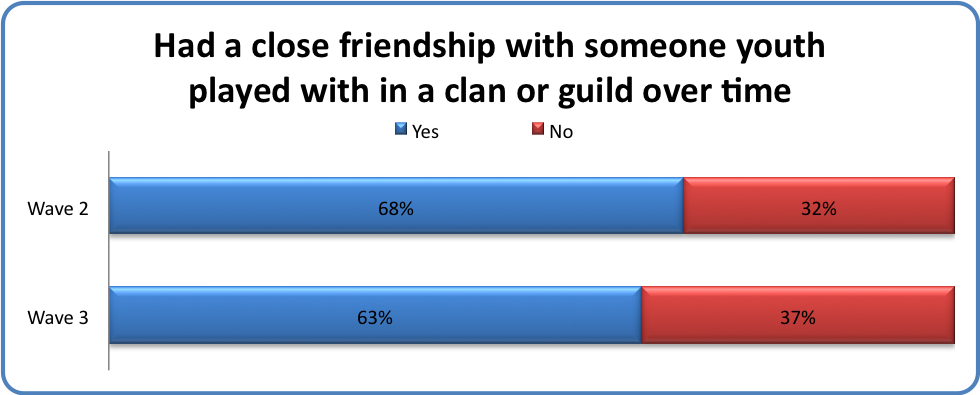

Most clan and guild members had at least one close friend in the game.

A close friendship was defined as a relationship with someone youth felt that they could talk online with about things that were really important to them (Finkelhor, Mitchell, & Wolak, 2000). Almost two in three youth said that they had a close friend in the game (see the Figure on page 23). This bond is likely a major reason why youth are part of these groups, and perhaps it acts as a form of social support more generally in one’s life.

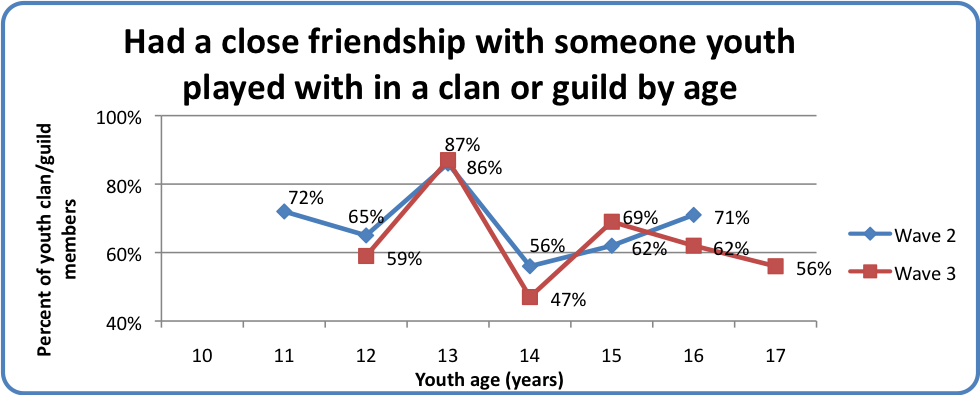

Trends by age are similar across time, but are difficult to interpret as they increase and decrease without an obvious pattern. With 85% saying that they have a close friend in the guild or clan, it seems clear that 13-year olds are the age group most likely to form an online bond.

CONCLUSION:

If adolescent and public health professionals are to prepare for the new challenges presented by emerging media, we need to have a basic understanding of what a typical media diet looks like for today’s youth. Our data, along with data from other national surveys conducted around the same time (Lenhart, 2009; Rideout, et al., 2010), suggest that media plays a monumental role in the lives of youth today. While the online world and interactive communication tools, such as text messaging, are transforming the experiences and relationships of youth, older technologies, such as television, continue to be the most common sources of media exposure for youth. Thus, as we endeavor to keep up with the evolution of media and technology, we must remember to place these changes into context of existing mediums.

REFERENCES:

Finkelhor, D., Mitchell, K. J., & Wolak, J. (2000). Online victimization: A report on the nation’s youth. Alexandria, VA: National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. Retrieved from: http://www.missingkids.com/en_US/publications/NC62.pdf

Lenhart, A. (2009). Teens and Mobile Phones Over the Past Five Years: Pew Internet Looks Back Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/14–Teens-and-Mobile-Phones-Data-Memo.aspx

Rideout, V., Foehr, U. G., & Roberts, D. F. (2010). Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8- to 18- year olds. Menlo Park: Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from: http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/8010.pdf

This bulletin was prepared jointly by (in alphabetical order): Dr. Josephine Korchmaros, Ms. Elise Lopez, Dr. Kimberly Mitchell, Ms. Tonya Prescott, and Dr. Michele Ybarra.

Acknowledgements:

The GuwM Study was funded by a Cooperative Agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U49/CE000206; PI: Ybarra). Points of view or opinions in this bulletin are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of policies of the Centers for Disease Control.

We would like to thank the entire Growing up with Media Study team: Internet Solutions for Kids, Harris Interactive, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and the CDC, who contributed to the planning and implementation of the study. Finally, we thank the families for their time and willingness to participate in this study.

Suggested citation: Center for Innovative Public Health Research (CiPHR). Growing up with Media: Media Use Patterns. San Clemente, CA: CiPHR.